The DMCA Censorship Tactic Scrubbing Criticism From the Internet

Shady actors are using fake copyright complaints to vanish negative press from the internet. The law is helping them do it.

This article is an accompaniment to an earlier article published by Scamurai called “How WikiFX Uses Copyright Takedown Complaints to Bury Criticism”. Read the original piece here.

Criticism of the forex review site WikiFX has repeatedly disappeared from Google Search results, thanks to DMCA copyright complaints filed by fictitious companies making bogus claims.

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) was passed in 1998 as an amendment to U.S. copyright law. It aimed to address the rise of the internet and brought the U.S. in line with two World Intellectual Property Organization treaties from 1996.

To put it in context, the law predates Google, social media, and smartphones. In 1998, only 3.6% of the global population (around 147 million people) used the internet.

One key part of the law limits liability for platforms like Google or YouTube when users upload infringing content — as long as the platform doesn't have "actual knowledge" and has a process for removing it once notified.

The DMCA lets copyright holders file takedown notices to give platforms "actual knowledge" of infringement. If a platform doesn’t act, it risks legal exposure. Most aren’t keen to take that chance.

From the beginning, there were concerns about how the DMCA would impact freedom of expression online. it proved prescient. Companies have used DMCA complaints to silence others for years — including coders exposing vulnerabilities, journalists and artists selling images containing their products.

Corynne McSherry, legal director at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, said the organization has been documenting this kind of abuse for decades. “A DMCA claim is one of the few and far too easy ways to use U.S. law to get material taken down quickly, with no prior judicial review."

How the DMCA Became a Censorship Tool

The DMCA takedown system is easy to exploit. Platforms don’t require evidence — just a form submission. Many err on the side of caution, taking content down automatically when a complaint is filed.

Often, these claims misuse the concept of "fair use." This legal doctrine allows limited use of copyrighted material without permission for purposes like criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching or research.

For example, in 2023, a video of actor and graffiti artist David Choe discussing an incident that resembled sexual assault went viral. Journalist Aura Bogado shared the clip, in which Choe referred to himself as a "successful rapist". Choe filed a DMCA complaint, claiming copyright infringement. X (formerly Twitter) took it down. Many argued the use was clearly fair use.

When it comes to media, many cases revolve around “fair use” and whether the news organisation has the right to use images taken from, for example, social media.

But in other cases, the claims are outright fraudulent.

The Washington Post has reported on Eliminalia, a reputation management firm that sent thousands of fake DMCA claims between 2015 and 2021 to erase negative press. Their method was to claim the content was stolen from fake websites.

The Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project uncovered a similar scheme by oil lobbyists and officials in Equatorial Guinea, who used the DMCA to remove critical reporting about their activities from South African news outlets.

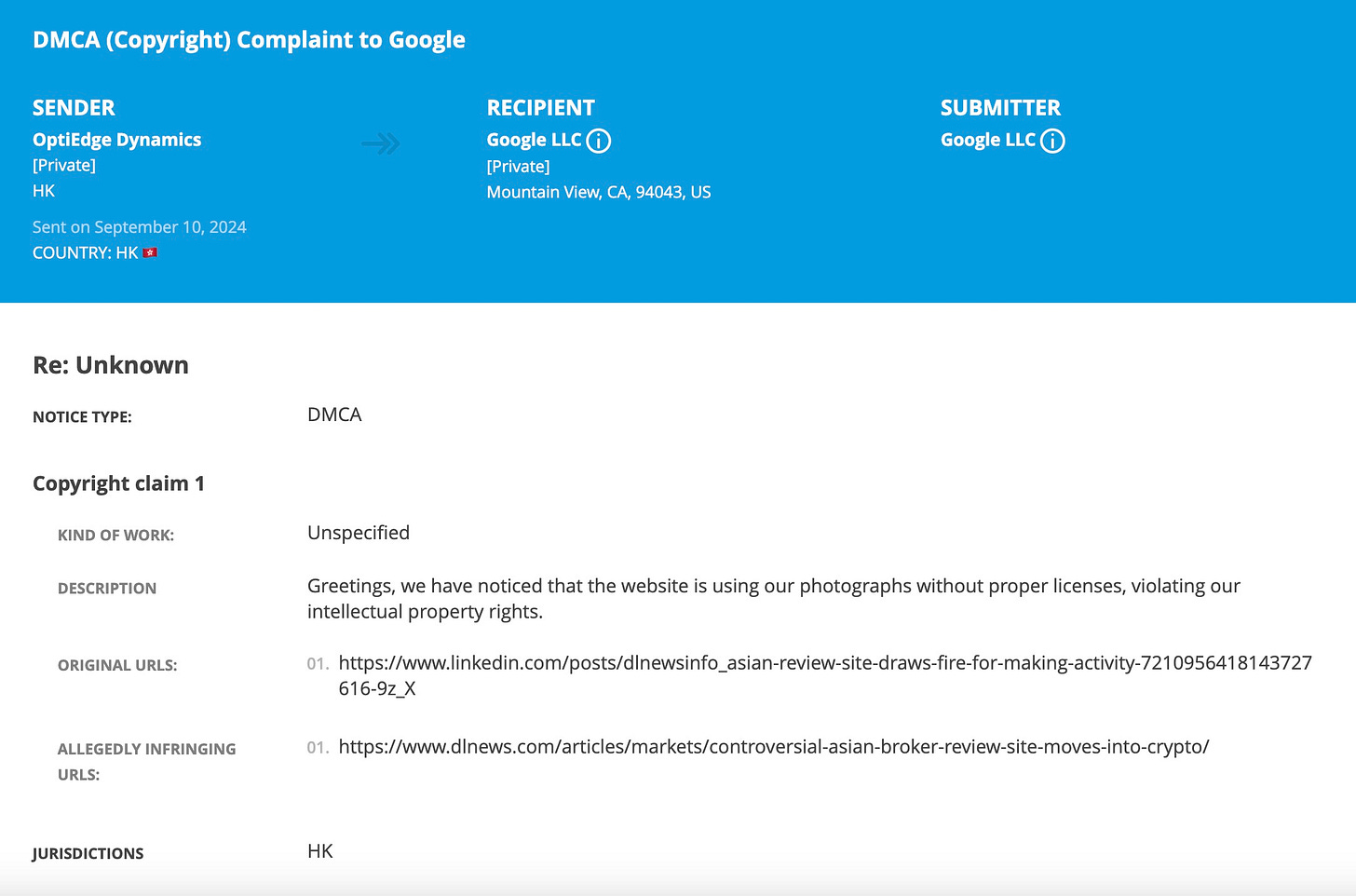

And in the case reported by Scamurai, a company called OptiEdge Dynamics filed a takedown claiming ownership of a Shutterstock image on a social media post promoting the article. The company doesn’t appear to exist, but the takedown succeeded. The company that the article discussed, WikiFX, has had multiple critical websites removed from Google Search, all filed by fictitious companies.

A Broken System for Fighting Back

There are ways to challenge a takedown, but the process is messy. Platforms aren’t required to reinstate content — and many don't.

A popular recipient of these complaints, Google enforces a 10-business-day waiting period to restore content. If the complainant doesn’t file a lawsuit in that time, the content may be restored. But that delay invites intimidation and legal threats. And even temporary takedowns can gut a story’s impact in a fast-moving news cycle.

Most individuals and small publishers don’t have the resources to push back.

According to Meredith Rose, Senior Counsel at Public Knowledge, laws that theoretically punish false claims are effectively useless. “The practical result is that the only actors who have any meaningful chance to push back against bad notices are the platforms themselves, and most of those are going to err on the side of caution and comply,” she said.

McSherry added that while DMCA abusers can be sued, victims must prove the complainant knew the claim was false — a high bar that's often prohibitively expensive to meet.

Google's Take

Google told Scamurai it takes fraudulent notices seriously. The company said most DMCA removals come from rightsholders with a history of valid claims and that it aims to balance ease of reporting with preventing abuse.

“We track abusive takedown requests, and when we become aware of entities or networks that are frequently requesting fraudulent takedowns, we apply extra scrutiny. Where appropriate, we’ve taken legal action to fight bad actors,” a spokesperson said.

Google submits DMCA notices to the nonprofit Lumen, which tracks takedowns and publishes a transparency report. But even accessing Lumen’s data can be frustrating. Users are limited to one filing per email per day. Though Lumen says it offers more access to researchers and journalists, it did not respond to a request for this from Scamurai.

Policy Changes

Rose at Public Knowledge said more could be done on a policy level, including introducing meaningful financial penalties for bad faith notices. At present, those that files repeated fake notices face few consequences.

There are currently no penalties for platforms that ignore legitimate attempts by individuals and companies to get their content reinstated. "That should change; put-backs should be mandatory," she said.

She also believes greater transparency in DMCA reporting would be hugely helpful. "Right now, small and medium-sized platform operators have to rely on personal experience and word of mouth to know which senders are bad actors. Better transparency on notices would allow for more robust analysis on who's using the system, why, and where the vectors of abuse are coming from," she said.

Until then, the DMCA remains a powerful tool — not just for protecting rights, but for silencing critics, hiding scams, and rewriting the internet’s memory.

About Scamurai

Scamurai Research is an investigative outfit based in Hong Kong focusing on scams, fraud, and consumer rights online.

It also offers services including private research projects and data collection related to cryptocurrency, fraud and corporate investigations.

Scamurai is fiercely independent. No puff pieces. No PR fluff. No sponsored content. It will not take money to shill your shitty projects.

Have a tip or want to collaborate? Email callan@scamurai.io.