How WikiFX Uses Copyright Takedown Complaints to Bury Criticism

Fake companies and fraudulent takedowns: a WikiEXPOSÉ on a shady forex empire and its disappearing act on Google Search.

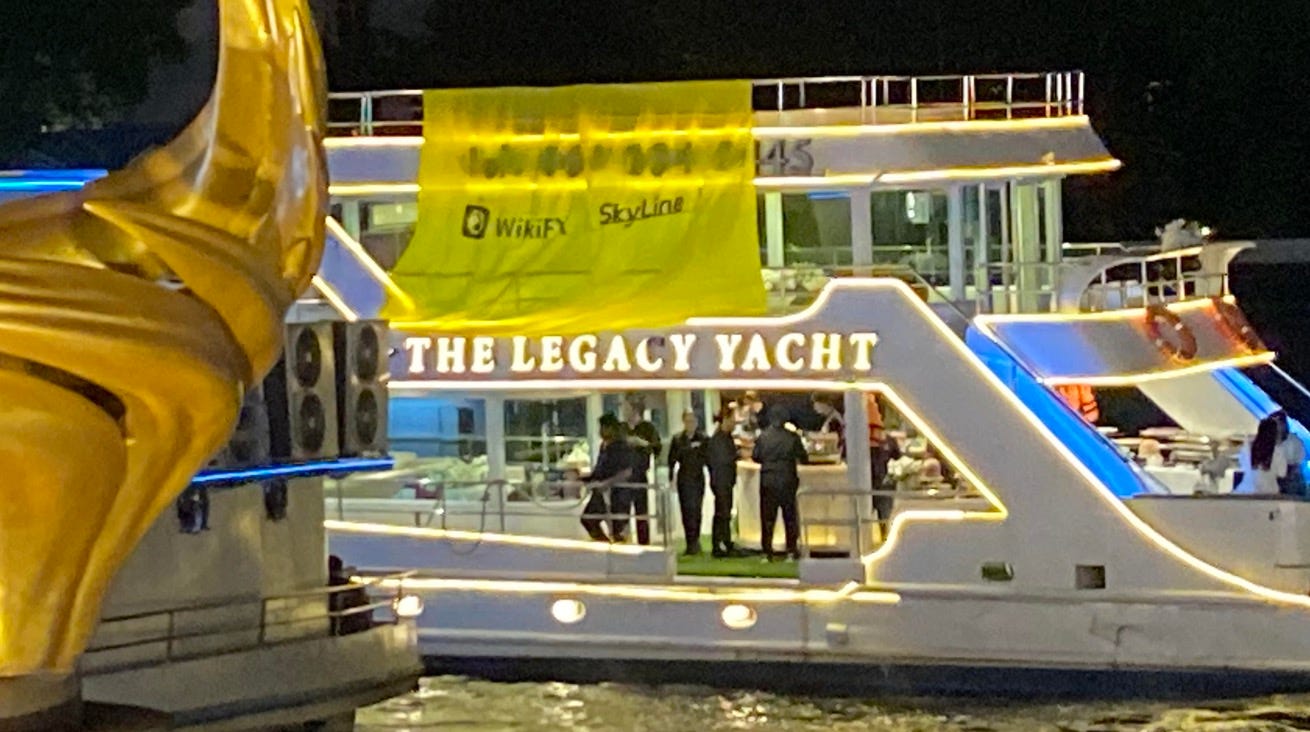

Ahead of a WikiEXPO conference in Hong Kong last week, I tried to dig up an article I wrote last year about their sister company, WikiFX.

Titled “Asian review site draws fire for ‘making scam brokers look legit’ — now it’s moving into crypto”, the piece detailed how WikiFX and its crypto counterpart WikiBit published fake reviews, pressured brokers for payment to boost ratings and promoted sketchy platforms, including some tied to pig butchering scams.

But no matter what I googled, I couldn’t find it. It still existed on the publisher DL News’ website, but as far as Google was concerned, it had vanished.

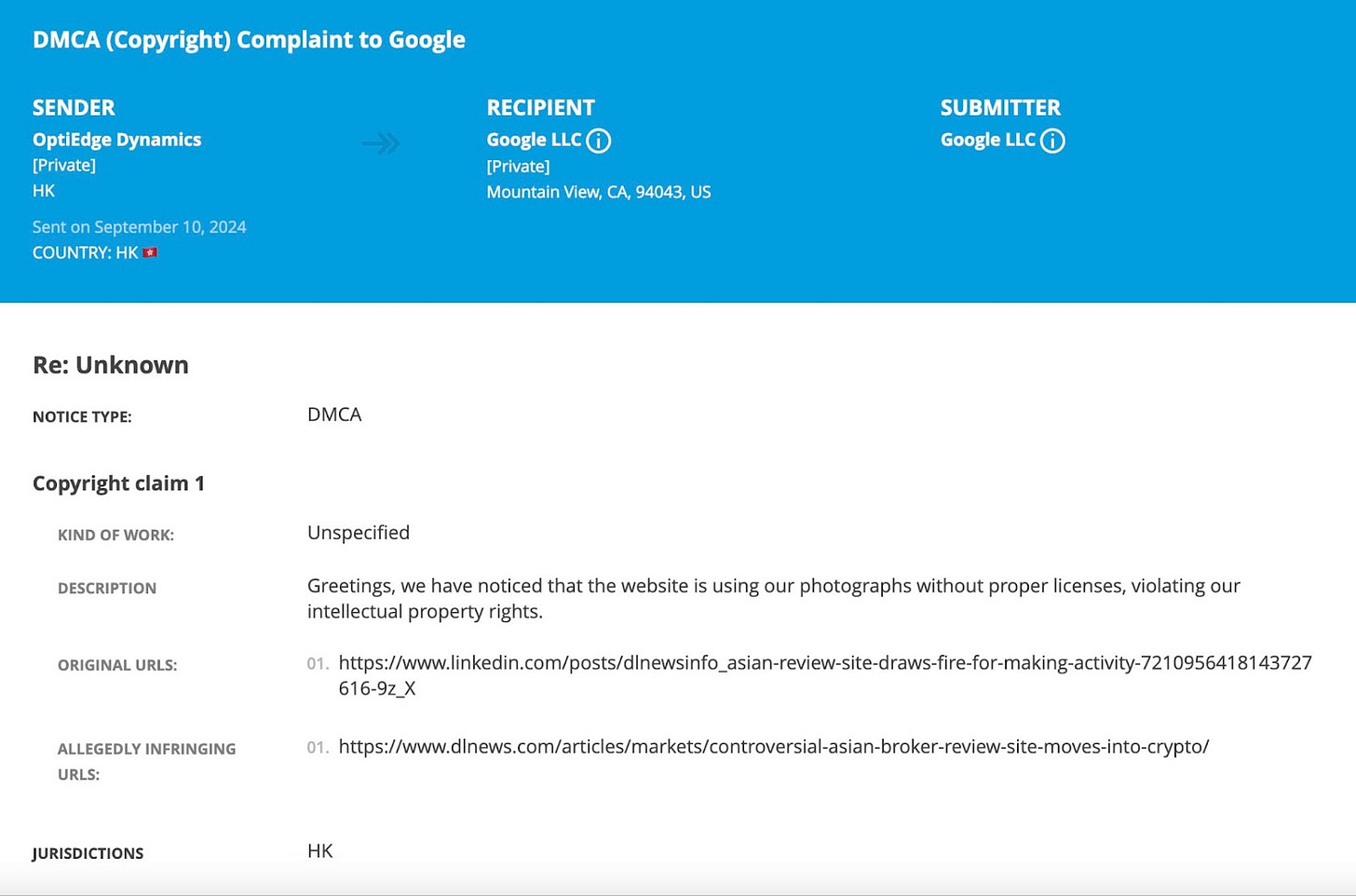

I later discovered the article had been delisted from Google Search results under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), a U.S. law from the late '90s that lets copyright holders request removal of infringing content from platforms like Google.

The complaints system for copyright infringement is ridiculously easy to exploit. No proof is required upfront, and once a complaint is filed, the content is often taken off Search automatically. It’s a convenient weapon for companies looking to silence critics under the guise of copyright protection.

The complaint, filed by a Hong Kong-based company called OptiEdge Dynamics, alleged that the article used its copyrighted images without permission. Yet, the only image included in the piece was a licensed Shutterstock photo.

The more I investigated, the weirder it got. OptiEdge Dynamics doesn’t exist. It doesn’t appear in Hong Kong’s business registry, nor does it have any online presence.

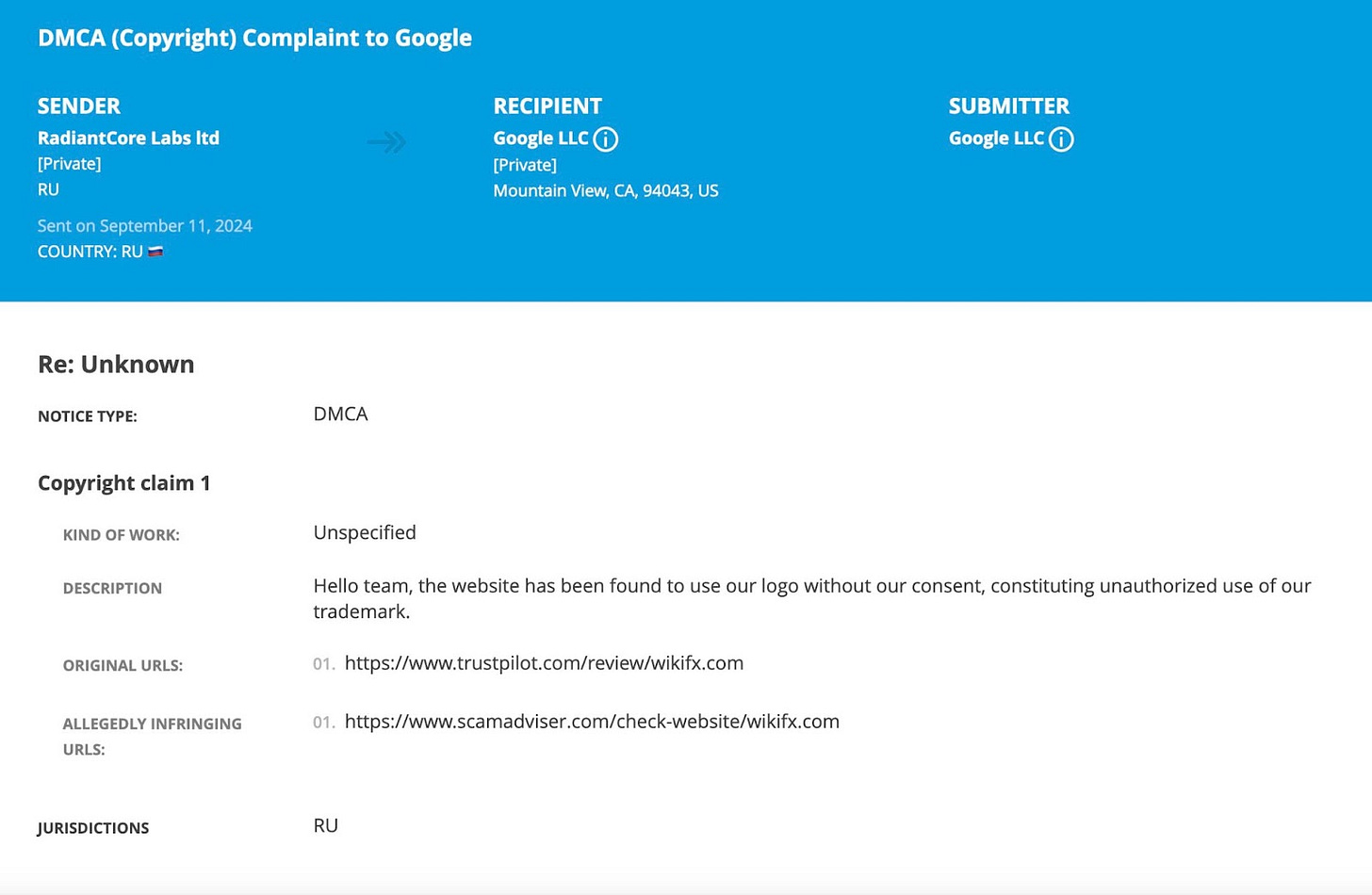

Then I found other phantom companies like VectorEdge Labs and SynergyNext Ventures filing similar DMCA complaints around the same time.

“It appears mysterious actors are trying to remove content they don't like from Google Search, and it's working,” Trista Kelley, editor-in-chief of DL News, said via email. “This obviously hurts our traffic and brand awareness, but worse, I fear it helps criminals hide their scam tactics from potential victims.”

All the takedown requests had one thing in common: they targeted criticism of WikiFX.

The WikiGlobal Empire

WikiGlobal is the parent brand behind a constellation of platforms including WikiBit, WikiStock, WikiTrade, and its conference wing, WikiEXPO.

But its flagship is WikiFX, which bills itself as a "leading global third-party forex industry information service platform."

Different sources reference various locales as its base, including Hong Kong and Singapore, while WikiFX’s service agreement makes reference to following the “relevant laws and regulations of the People’s Republic of China”. WikiBit gives an address in Shanghai.

Despite multiple emails to WikiEXPO, WikiFX, WikiBit and WikiGlobal, no one responded to a request for comment for this article.

WikiFX’s user numbers are fuzzy. Its website claims 21 million across 180 countries and listings on 49,000 forex brokers. Promotional materials from the recent WikiEXPO conference — which included speakers from HSBC, Animoca Brands, Galaxy Digital, and Tron — boasted 210 million registered members and 64,000 broker reviews. That would put it in Discord territory in terms of user numbers.

It also claims over a billion social media followers.

My article was just one of several targeted in a wave of DMCA takedown requests last year.

To file such a request, Google requires the complainant to provide both the offending URL and the URL where the original material allegedly appears. In my case, the so-called "original" source was a LinkedIn post by DL News sharing the article — implying DL News had stolen from itself.

Other targets included the website Broker Review FX, which called WikiFX a "scam review website"; a LinkedIn user who shared an article titled "WikiFX Blackmails Brokers and Writes Fake Reviews”; and a review site that rated WikiFX 3.3 out of 5.

In each instance, WikiFX wasn't listed as the complainant. Instead, fake company names were used. But in one case, a supposedly Russian outfit named RadiantCore Labs claimed infringement based on the use of "our logo", referring to the WikiFX logo on a site criticising it.

Finding Recourse

This isn’t a new trick. Reputation management firms have long used DMCA complaints to censor unflattering content. Some even advertise services like "bury negative news" or "clean your online image" using cookie-cutter legal threats.

Corynne McSherry, legal director at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, said DMCA abuse is all too common. “A DMCA claim is one of the few and far too easy ways to use U.S. law to get material taken down quickly, with no prior judicial review,” she told Scamurai. “We’ve been documenting DMCA abuse for decades because every false claim means lawful speech is taken offline.”

The nonprofit Public Knowledge told Scamurai that the scope of abuse is hard to quantify. There aren’t many studies on the topic, particularly when it comes to fraudulent requests. One 2016 study found that about 1 in every 14 takedown request raised a fair use question, half of which were directed at news sites.

Outlets like DL News, which use Google Console, at least get notified of takedowns. Social media posters, who don’t own the platforms they post on, don’t even get that.

Recipients of a takedown notice can file a counter-notice, but the system is clunky. DL News tried to submit one recently but couldn’t navigate Google’s tools due to issues with entering the reference ID, a common issue.

Even if a counter-notice is filed, content only gets restored if the complainant doesn’t initiate legal action within 10 business days. That potentially opens the door to more threats and costs for the victim.

In theory, McSherry said, a victim of a fraudulent claim could take a DMCA abuser to court. But courts generally require proof the abuser knew the claim was false, which is hard — and expensive — to establish.

A Google spokesperson told Scamurai the company complies with the law and takes abuse seriously. “We track abusive takedown requests, and when we become aware of entities or networks that are frequently requesting fraudulent takedowns, we apply extra scrutiny to such requests,” the spokesperson said. “Where appropriate, we’ve taken legal action to fight bad actors abusing the DMCA.”

Want to understand more about how all this works? Check out this explainer on DMCA takedown abuse.

About Scamurai

Scamurai Research is an investigative outfit based in Hong Kong focusing on scams, fraud, and consumer rights.

It also offers services including private research projects and data collection related to cryptocurrency, fraud and corporate investigations.

Scamurai is fiercely independent. No puff pieces. No PR fluff. No sponsored content. It will not take money to shill your shitty projects.

Have a tip or want to collaborate? Email callan@scamurai.io.