A random number added me to a Spotify fraud group. Here’s how they work.

"What may look like an innocent job could inadvertently amount to complicity in a money laundering operation."

Any Hong Kong resident will know that scam calls and being added into random dodgy-looking group chats are a routine part of everyday life.

According to the Hong Kong Police Force, deception crimes accounted for 44% of all crimes last year, more than any other crime, and involved over US$1.5 billion of victim funds.

Most of these fraudulent communications are trying to steal your money, rather than offering you some.

But one day in June, almost like a breath of fresh air from all the desperate attempts trying to convince me that my “Douyin [Chinese TikTok] account had been hacked”, I was added into a WhatsApp group that had a far more interesting, though illicit, purpose.

Sporting a group image of a genuine Spotify podcast for added legitimacy, the group had 83 members.

This may ostensibly seem to be an innocent, albeit unusual, business model where people can make money listening to music. But the reality is far more sinister.

In fact, there are two fraudulent activities that these groups typically perform:

1. To game the popularity of certain artists of tracks, providing them “listeners” in return for money – similar to buying followers on social media

2. To launder criminal money by paying artists to produce content, and then collecting Spotify royalties from fake listens (of which a small proportion is then paid to the “listeners” in return for their “work”).

Spotify money laundering? What?

This may indeed sound a little far-fetched. Let me explain.

It doesn’t take too much time to upload nonsense to Spotify, and with every listen and follow, the uploader gets royalties.

An investigation in Sweden last September found that criminals there were using this method to launder money.

Criminals will pay complicit artists to produce tracks with dirty money. They will then invite individuals to listen, follow and like those artists and their content.

The royalties generated are then received by the criminals and duly reported to the relevant tax offices as legitimate earnings from Spotify.

“Integrity is at the heart of our operation”

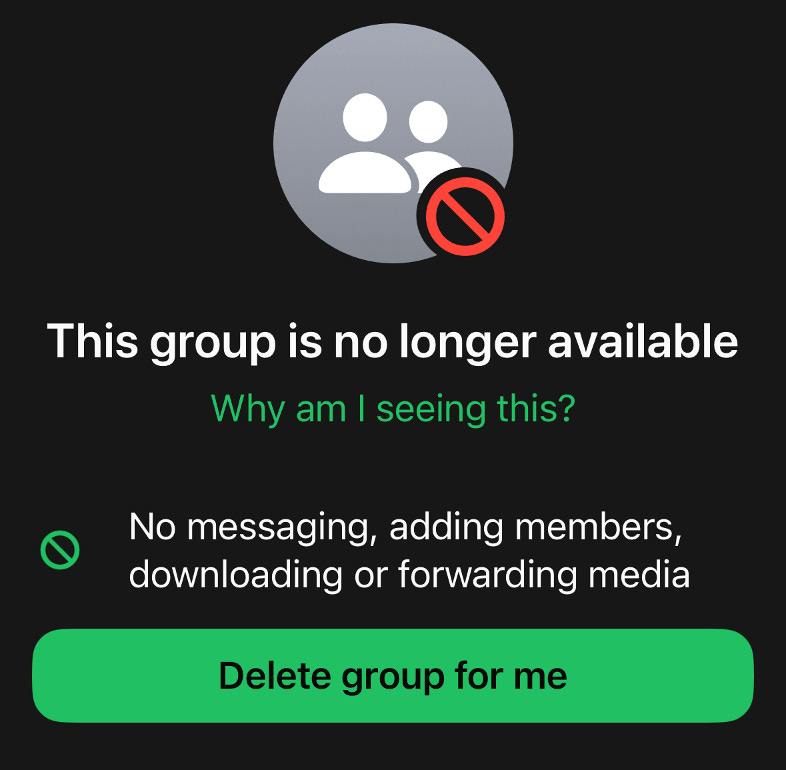

I was added (randomly and against my will) to this group at the same time as many of its 82 other members, and the entire operation lasted just two days before WhatsApp shut it down.

The fast reaction of the moderators is commendable. Similar swift action is needed on the fronts of Spotify and banks facilitating these payments.

Being a bystander throughout those two days, however, provided interesting insights into how these groups work.

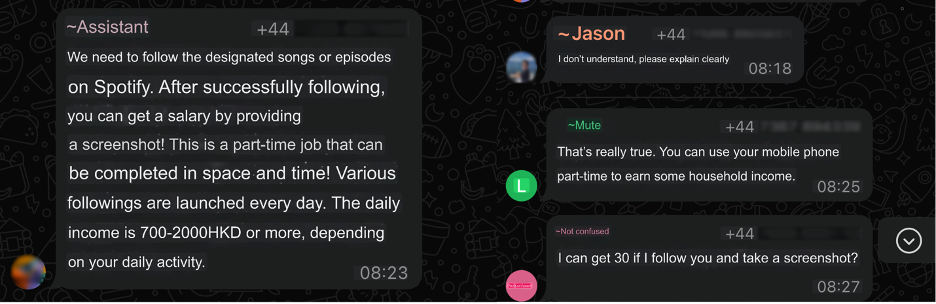

First, we were all introduced by a certain “Assistant”, to the too-good-to-be-true idea that we could earn anywhere between HK$700 to HK$2,000 (US$90 to $257) simply by listening to Chinese rap.

Each listen would generate HK$3 (US$3.80), and there would be approximately 50 tracks posted every day. All communication was in Mandarin, though the promise of Hong Kong dollars suggests that this group was targeting individuals specifically in Hong Kong.

That said, the vast majority of member phone numbers within the group were from India and Indonesia.

The admins, however, were all using +44 numbers from the UK. The UK is rather unique in not requiring phone numbers to be registered to an identity. Prepaid sim cards can be bought – often in bulk – from stores without any ID.

The group also has some sort of invite link somewhere – presumably a Hong Kong-specific messaging board – as that is how a large number of these numbers joined.

Soon after joining, the administrators began talking up the “job” opportunity as a stable side income, emphasising “integrity [was] at the heart” of their operation.

Responses by members suggest that they were not aware of the fraudulent nature of the work. Some did not even have Spotify downloaded.

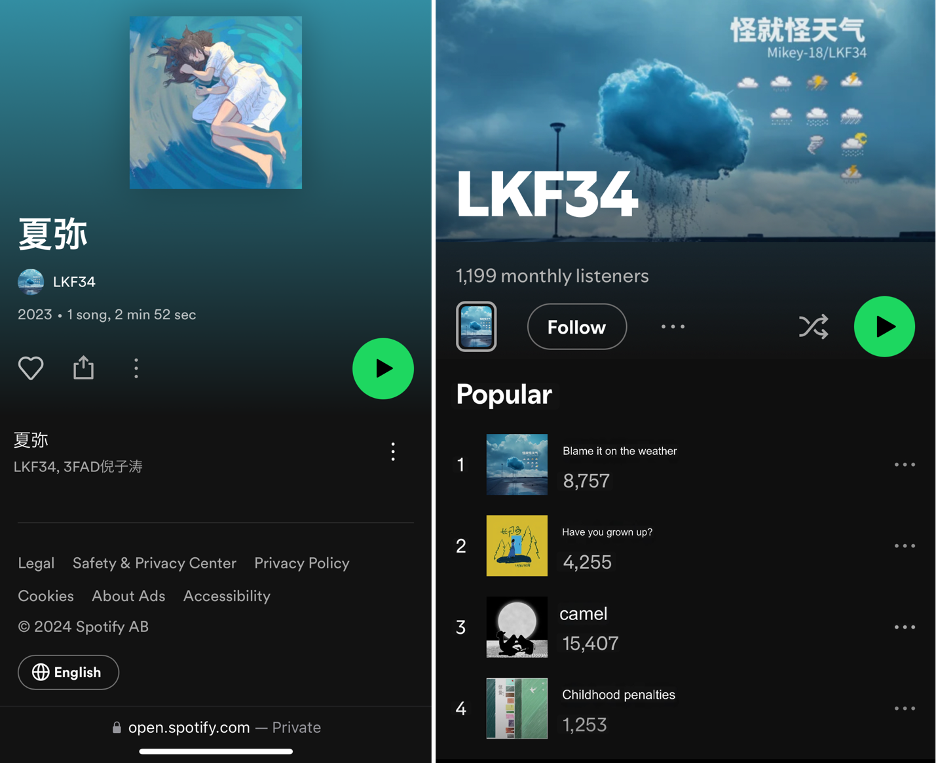

The group administrators tried to ease sceptical members into the idea through a “test task”, a common tactic in employment frauds. The “task” involved a link that led to a Chinese rap song, published by an artist with 1,199 monthly listeners. Members were instructed to like and listen. Likes removed before 24 hours, warned the admins, would not be rewarded.

The song itself was published by an anonymous artist using what seemed to be an AI-generated album and track covers.

When looking into what “fans also like”, Spotify reveals a rather large web of very similar artists and tracks – all avoiding the use of actual names or images of themselves.

This particular “test task” artist has 33,622 listens – translating to about US$168 worth of royalties.

This raises the question of how “profitable” this fraud operation is if it can pay people US$3.80 per listen.

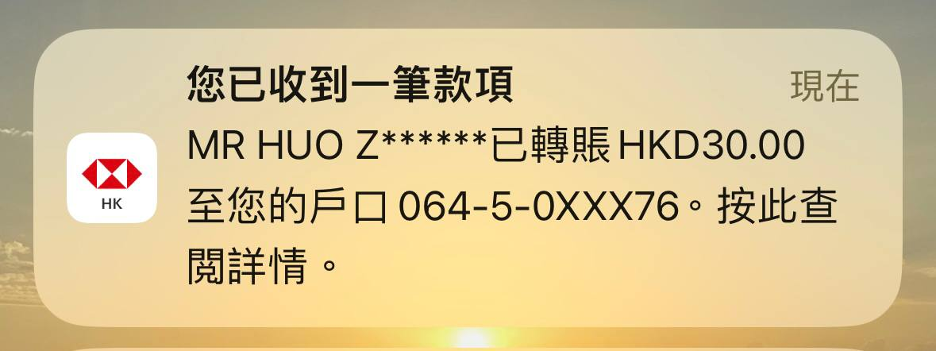

Images claiming to show bank transfers to participants are routinely posted into the channel to shore up a sense of legitimacy.

It is possible that this group is a scam in itself – hoping to amass listens for fraudulent tracks with no intention of actually paying anyone.

Alternatively, the invitation to a closed group for serious participants suggests that an initial HK$30 payment may be bait to take part, with payments soon becoming smaller and more realistic.

Spotify-related fraud is not new. But it is a niche facet of crime. What may look like an innocent job could inadvertently amount to complicity in a money laundering operation.

About the author: Eray Arda Akartuna is an assistant professor of crypto and future crime at City University Hong Kong (CityU) and a senior cryptocurrency threat researcher at blockchain analytics company Elliptic.